Monday, March 2, 2015 by Hunter Johns

A wise AP music theory teacher recently related to me the thesis of Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell’s book on success. The gist of it went that no creative person ever makes anything truly masterful until they have put in about ten thousand hours of work. The theory, as told to me, is that Mozart might have made incredible music from the time he was five, but his greatest work came when he was in his early thirties, after he had put in his ten thousand hours. Moreover, The Beatles spent night after night in Liverpool’s Cavern for a few years before hitting it big, and Michael Jordan made three runs at the title. Like any number of successful people, they’ve all, apparently, put in astronomical amounts of time into their craft, and been paid back in full.

While the speech was an (admittedly effective) appeal to get us to practice more often, I’ve thought a lot about what it really means to be a creative person, or an athlete, or any other person worth being, before we reach that ten thousand hour threshold. My initial vision of this “ten-thousand-hour workout plan” is me trapped in the proverbial woodshed, unwashed and haggard, practicing my instruments until my fingers fall off, unable to show the world my work until I’m thirty-something and my ten thousand hours have been logged.

With a little more thought, however, I realized that isn’t how it has to be. The ten thousand hour threshold isn’t some binary; I’m not completely incompetent at nine thousand nine hundred and ninety nine hours, and an hour of practice later I’m one of the greatest musicians of all time. I’m going to be good along the way; my music will most likely be worth listening to at one thousand hours, just as it will at five thousand and nine thousand.

Why do people go to minor league baseball games? Why do people watch college football, or college basketball? Why do people buy records from young, relatively inexperienced musicians or go to their shows? In my experience, people don’t like to pay money for things they don’t want to have or do. It must be, then, that watching athletes before their prime or listening to music from musicians pre-mastery is enjoyable. Judging purely from Gladwell’s standards, almost every artist in Billboard’s top ten last week (February 17-23) has not realistically put in ten thousand hours of work. Here’s a list of artists in the top ten with their ages:

1. “Uptown Funk!” Mark Ronson, 39; Bruno Mars, 29

2. “Thinking Out Loud” Ed Sheeran, 24

3. “Take Me To Church” Hozier, 24

4. “FourFiveSeconds” Rihanna, 26; Kanye West, 37; Paul McCartney, 72

5. “Sugar” Maroon 5 (Adam Levine), 35

6. “Love Me Like You Do” Ellie Goulding, 28

7. “Blank Space” Taylor Swift, 25

8. “I’m Not The Only One” Sam Smith, 22

9. “Lips Are Movin’” Meghan Trainor, 21

10. “Style” Taylor Swift, 25

Just to show my work here, if you begin practicing at five, and practice one hour every single day without getting burned out, sick, or something along those lines, you’ll get to ten thousand hours by the time you’re thirty three or so. (Realistically, all the artists on the singles chart have probably spent and continue to spend much more than an hour a day practicing, the numbers are just for perspective.) Assuming, however, that a musician achieves mastery around their early thirties or so, few of those on the chart (all except Ronson, Kanye, McCartney, and Maroon 5) would be worth listening to if you judge music in my scary “woodshed” binary I mentioned earlier. Nevertheless, as any pre-teen girl will tell you, Meghan Trainor is pretty good, despite her young age.

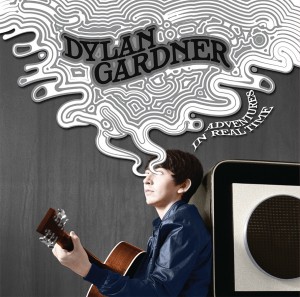

Warner Bros. Records via Moxie

If I were to give Dylan Gardner a pass this round just because he’s younger and less experienced, I would be doing everyone—me, you, the music industry, Dylan Gardner—a disservice. Mediocre music is mediocre music, whether made by an eighteen year-old or a seventy eight year-old. And while a discussion about what mediocre music even is might be a whole different topic, you have to be the ultimate judge for yourself as to whether Dylan Gardner deserves your $9.99 as much as Paul McCartney and Rihanna do (I can definitely tell you Kanye doesn’t care either way). Look Gardner up, give his record a listen if you‘re feeling it. Maybe it is a waste of your time, or maybe you see something in it. Moreover, maybe you think he’s a contender right now, as he is.

Whatever your reaction may be: consider listening to it, weighing it against someone established, someone who’s put in their ten thousand hours, and then decide for yourself if Dylan Gardner has what it takes to stay in business long enough to put in his own ten thousand.

Adventures in Real Time was released on May 13 by Warner Bros. You can get it at iTunes or Amazon.

Hunter Johns is a junior covering music for The Lightning Rod.

This reviewer has my attention.